Covenant Postmillennialism

Ray Sutton | 1989

Then He said, "What is the kingdom of God like? And to what shall I compare it? It is like a mustard seed, which a man took and put in his garden; and it grew and became a large tree, and the birds of the air nested in its branches."

And again He said, "To what shall I liken the kingdom of God? It is like leaven, which a woman took and hid in three measures of meal till it was all leavened." (Luke 13:18-20).

Hal Lindsey was wrong. Several years ago he made the comment at the beginning of his little potboiler, that a view of the future known as postmillennialism was all but dead. He was wrong, as this newsletter obviously disproves. Postmillennialism is alive and well on the great but-not-so-late planet earth, to put a twist on another title of one of Lindsey’s books. Ironically, postmillennialism was just beginning a resurgence at the time of Lindsey’s statement. He couldn’t see it, however. Neither could many of his colleagues. Yet, not so any more. They all see it now, but it’s too late to stop the new tide of optimism from coming in. Postmillennialism is back and I believe that it is here to stay.

What Is Postmillennialism?

The eschatology known as postmillennialism has been so battered and abused by its antagonists that we need to define terms. We should understand what it says, know the difference between humanistic and theistic optimism, and even consider the number of views (nuances) within the camp. For example, there is a difference between revivalistic postmillennialism and covenantal postmillennialism. There is a distinction between classic postmillennialism, the kind the Puritans held, and progressive postmillennialism, the newer Christian Reconstructionist type of postmillennialism. Do you know the differences? It’s not as though your salvation depends on it, but the fact that I can discuss these kinds of distinctions proves that we’re dealing with a very sophisticated and highly developed shift within the evangelical camp.

The evangelicalism of the 20th century has largely subscribed to some brand of premillennialism. Historic premillennialism simply believes that Christ will come before the millennium and set up His kingdom. Dispensational premillennialism is a bit more complicated. It has three versions depending on when the rapture occurs, a secret event in which the church is removed from the earth. The rapture of the saints before the tribulation is pre-tribulationalism. The rapture in the middle of the tribulation is mid-tribulationalism. And, you guessed it, the rapture after the tribulation is post-tribulationalisrn.

I should add that there have been and are a number of amillennial evangelicals, those who believe the millennium is in heaven and not on earth until after the return of Christ. Again, the key word is after. But there are good and bad versions of amillennialism. The bad type in my opinion comes very close to the premillennial view of history. It believes that the Church will become weaker and weaker until it has to be rescued by some sort of rapture. On the other hand, there is a better type of amillennialism that comes very close to the newer, revised type of postmillennialism. It’s called optimistic amillennialism. This view teaches that the church will continue to grow and have victory but that the fullness of the millennium will not come until the Second Coming. So far so good, but optimistic amillennialism has not been the predominant view embraced by evangelicals. Negative millennialism captured the day several decades ago.

Now, however, a major transition is occurring in evangelicalism. I hear all the time from evangelical who are B. O. R.E.s, short for ‘(Burned Out on the Rapture Evangelicals.” They’re most often people who have been converted within the last twenty years, and who are tired of being constantly cranked up by some crazy date-setter. They no longer want to be told the next antichrist, only to discover that the rapture dates and the antichrists are wrong. Enter postmillennialism. It is sweeping through every major evangelical seminary, even the premillennial ones.

I also regularly hear how this position is a breath of fresh air. I’m told by so many of a renewed interest in the Bible and even eschatoiogy. This signals the fading of premillennialism and a new-but-not-so-new wave rolling through the church, for postmillennialism dates back at least to the Puritans and I believe further back to the early church in its incipient forms.

So what is postmillennialism? In summary, postmillennialism advocates a return of Christ after the conquest of the kingdom of God over the whole earth. The following time line shows the position.

Death/Resurrection/Ascension | Millennium | Return of Christ

Notice that Christ does not return until after the millennium, hence postmillennialism.

Yet, even within postmillennialism there are different views of the millennium. For example, classic postmillennialism builds on the verse, “With the Lord one day is as a thousand years and a thousand years as one day” (II Peter 3:8). It sees history as based on the model of the creation week. Each day of history is one thousand years. Given Bishop Ussher’s chronology, history is nearing the end of the sixth day of time; the sabbath millennium is about to begin. Thus, the millennium is a literal one thousand years.

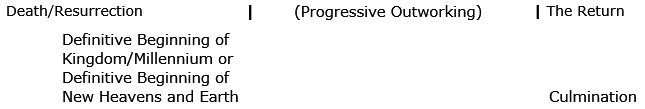

Many good men have held classic postmillennialism and many Christian Reconstructionists do today. But there is another view of postmillennialism that encompasses some aspects of amillennialism. I call it progressive postmillennialism. It does not believe in a literal one thousand year millennium. Instead, it takes a (millennial) figurative view of the millennium referred to in Revelation 20, meaning the millennium is not a fixed period of one thousand years but symbolic of an extended period of time. It also applies the model of personal sanctification (definitive, progressive, and culminative) to history. It sees the millennium as definitively beginning at the Cross, progressively working out in time, and culminating at the return of Christ.

Putting this together, progressive postmillennialism sees a definitive transformation of the world at the Cross, the definitive beginning of a New Heaven and New Earth [finally in 70AD with the destruction of the old heaven and earth. See this]. This is progressively worked out and comes to final culmination at the Second Coming. The following diagrams the position.

So there are sophisticated nuances to postmillennialism. There is even room for disagreement about these matters, as well as what happens shortly before the return of Christ after the kingdom has come in all its fullness. But the one common denominator among evangelical postmillennialist is their belief that Christianity will so pervade the world before Jesus returns that there will come a time when no one will need ask his neighbor if he knows the Lord because all will know Him from the least to the greatest (Hebrews 8:11).

Humanistic vs. Theistic

When I was in seminary, postmillennialism was described in the following paraphrased terms. “Postmillennialism was popular before World War 1. It believed that man would get better and better until the world was a perfect utopian society. The old liberalism of the 19th century taught that man was not completely sinful; he could improve himself. It was founded on Darwin who had used the same kind of teaching to build an evolutionary view of society, one where animal becomes man. If this could happen, then who knows to what extent man could evolve. And, who knows how far man could improve his environment.

“Under these influences, the church’s view of the future was affected. Through a faulty doctrine of man and his depravity the church began to teach that man was perfecting himself. It started to believe that man could reach a golden age. But then the great World Wars occurred. The Great Depression hit. Famine continued. Catastrophes didn’t stop. Postmillennialism died!”

Incredibly, this is what I was told. It was wrong. I don’t know of a single evangelical postmillennialist who has ever believed such nonsense. Fortunately, better providentially, a church history professor and a New Testament professor at the same seminary helped clarify the distinction between humanistic optimism, which I hesitate even to call postmillennialism, and theistic optimism.

What’s the difference? The contrast is in the words humanity and Deity, between God and man! Humanistic optimism teaches pretty much what I’ve paraphrased above. As the word “humanistic” implies, it is man-centered. It is based on bad theology. It is a modernistic view of man, teaching that man can bring peace to the world through his own efforts such as scientific development, the occult and the New Age Movement. Yes, this kind of optimism has died as a result of the covenant-breaking of Western man. But, theistic optimism hasn’t because it centers around God not man.

Theistic optimism is founded in God. It does not believe that man is getting better and better. It does not believe in the possibility of utopianism. It holds instead to the belief that God definitively conquered Satan and his army at the Cross. It sees as an extension of this victory and Christ’s Ascension the application of this conquest to the whole world. It believes that Christ will not come back until the kingdoms of this world have been made the kingdom of Christ. Then, when Jesus returns, He comes back to a victorious church and not a defeated one. So it is God who is triumphing on the earth, not man. It is God who has transformed the world, not man. It is God through His matchless Grace that completes the change, not man through his sinful works. This is all quite different from the old liberal kind of postmillennialism.

Versions of Postmillennialism

Triumphalism

Perhaps the greatest misconception of evangelical postmillennialism is its association with Charlemagne’s method of establishing Christianity in France.

Charlemagne (Charles the Great) was king of the Franks and first medieval Roman emperor in the 8th century A.D. One description portrays him in the following manner:

His greatest military achievement was the conquest of the Saxons in a protracted war that drained his resources. Victory was gained through massacres, forced conversions, mass deportations, and the organization of Saxony into counties and dioceses under Franks loyal to Charles.1

Unfortunately, this is the image that many evangelical have of postmillennialism. They perceive that if Christian Reconstructionists had their way unbelievers would be forced to convert and anyone who disagreed with Christian Reconstructionism would be deported or massacred. This is silly but this is definitely the perception out there in “radio land.”

A fellow called me the other day. The following is the conversation as closely as I can remember it.

Caller: “Hello, Dr. Sutton my name is

I am an evangelical and I have been reading Christian Reconstructionist material, I have a concern.”

Sutton: “Yes, I’m not sure I’ll be able to satisfy your concern but I’ll give it a try.”

Caller: “1 like a lot of what I hear and read. The ideas of Christian Reconstruction are powerful. I’m even almost persuaded on infant baptism. But the tone is harsh. It leaves me thinking that you people have a hidden agenda.”

Sutton: ‘Uh, what do you mean? [This is always a good thing to say when you don’t know what to say.] Can you give me an example? [This is usually even better because you can escape facing an admonishment by asking for details, but in this case, the caller was prepared.]”

Caller: “Well, I don’t know how detailed you want me to get, but it seems to me that all you people do is attack everybody else. I hear a lot of hostility and I’m wondering how you’d be if you were really in control. Take me as an example. I’m a Baptist. Would you compel me to become reformed and force me to have my children baptized? If I didn’t, would you deport me? Would you put me in the stocks? What would you do?”

Sutton: “I’m not sure where you’re getting these impressions. I recognize that this is your perception, but as far I know the writings of Christian Reconstruction have never taught a ‘Charlemagne approach’ to spreading Christianity. To answer you specifically, I don’t think that you should be compelled to believe anything. Furthermore, compulsory baptism would also be wrong. I do think that leaders should be required to be believers, Trinitarian in theology, before they can run for office but that is a far cry from what you’re talking about. As for some kind of hidden agenda, there isn’t any and I’m sorry that you’ve gotten this impression.”

I have thought long and hard about these kinds of impressions. Sure, I think Christian Reconstructionists can take some of the blame but not all of it. The leaders are mountain men types in theology; they’re pioneers. They’re great people to go into a battle with, but they’re not the kind you’d like to have next door. Why, if they didn’t start out like mountain men, they soon became this way. They acquired so many bruises from fighting all the battles that they sort of adopted an irritable personality. Also, there is a good bit of rhetoric. Much of the literature is designed to provoke a response. Right or wrong, these are my assessments.

But, I do know that none of the Christian Reconstructionist leaders believe in a Charlemagne approach to building the kingdom, doing evangelism or anything. I have read almost all of the Christian Reconstructionist material; that’s a major feat in and of itself. I challenge anyone to find stated in writing that Christian Reconstructionism teaches what Gary North has called a top-down-approach to evangelism; he in particular has devoted several pages of his writings to a bottom-up-approach. Yes, there have been those in the history of the church who have believed in coercion, Augustine being one of them. Christian Reconstructionism, however, does not!

This position also has historic precedent. It advocates rule of society by the institutional church. It developed as a result of the collapse of the Roman Empire just before the early Middle Ages. It’s fall left the West without leadership. The people turned to the Church’s leaders (Bishops and presbyters) for help. They wanted people they could trust and they had seen how The Church handled its courts and problems. They wanted ecclesiastical rulers because the civil rulers were so corrupt. They had seen the superior organization of the Church. They had benefitted from it. So, they thought that this kind of rule would bring in the kingdom of God.

The idea of the Church’s ruling society was not totally without some Scriptural basis. The Apostle Paul says,

And He [Christ] put all things in subjection under His feet, and gave Him as head over all things to the church, which is His body, the fullness of Him who fills all in all (Ephesians 1:20-23).

The key, however, is that Paul does not specify that the Church as an institution is to rule. Rather, he advocates the saints should rule, meaning the members of the Church. The difference is significant. Paul says Christians should and will dominate society. But, even if an ecclesiastical leader should end up in office, he should not serve as an official of the Church. Yet, even if he does serve, he should not be able to wield the sword and the sacrament at one and the same time. No one should have so much power that he can execute as well as excommunicate the same person. So the Bible allows the saints to rule without allowing for the institution to have control of political government.

Ecclesiastical postmillennialism came to its zenith when a pope made a German king wait three, cold, snowy days outside the pontiff’s castle door for forgiveness of a certain offense. (Tradition has it that there was a giant knocker on the door and the king paid servants to bang the knocker night and day. Finally, the pope relented because the sound was driving him crazy.)

Perhaps some might think that Christian Reconstructionism believes in ecclesiastical postmillennialism. Perhaps they would even point to the emphasis on the Church by some of Reconstructionism’s leaders. But none of these leaders to my knowledge believes in this kind of medieval triumphalism. They are convinced of the necessity for the saints to rule, but not for the institution of the saints to take over political matters. This distinction is the difference between ecclesiastical postmillennialism and covenantal postmillennialism.

In almost a reaction against these two kinds of postmillennialism, revivalistic postmillennialism sees no institutional expression of the millennium. It believes that the kingdom will come by means of revivals. This is the millennialism of Jonathan Edwards of the Great Awakening and other 18th century postmillennialist. Edwards spent much of his time tracking revivals around the world. He considered them to be the critical sign of the progress of the kingdom. He believed in their necessity in much the same way dispensationalists require the existence of the Nation Israel. Perhaps this explains the despondency in Edwards when the revivals suddenly stopped.

What is wrong with revivalistic postmillennialism? It is certainly not the understanding that the Spirit of God must change men’s hearts on a large scale. No, it is something much more basic. It errs in its failure to see the importance of the doctrine of culture. T. S. Eliot makes the point that it is impossible to carry out the Great Commission until the culture-at-large is converted.2 Very simply, our Lord said to “Disciple the nations” (Matthew 28:18-20). How can the nations be discipled, therefore, if a culture’s institutions are not brought under the Gospel and thereby encourage further evangelization? They can’t.

A friend of mine once called the most famous (revivalistic) postmillennialist of this century, Loraine Boettner. Whern many evangeticals think of postmillennialism, their attention is usually called to this great man, even though he is a revivalistic postmillennialist. My friend was entertaining the possibility of becoming a postmillennialist, so he gave Boettner a call. He had essentially one question. He entered the following conversation.

Friend: “Dr. Boettner, you are a postmillennialist?”

Boettner: “Yes, I have been for decades.”

Friend: “How do you believe the millennium will come?”

Boettner: “1 believe that a great revival will sweep the earth.”

Friend: “Yes, but how will you know when that great revival has come?”

Boettner: “1 don’t know, I never thought about that question before.”

End of the Conversation!

The problem with revivalistic postmillennialism is its failure to understand the objective manifestation of the Spirit’s subjective work in the heart of man. It does not understand the cultural side of the spiritual. It speaks of revivals apart from the social. Consequently, revivalistic postmillennialism misses one entire half of the eschatological picture.

Covenantal Postmillennialism

This brings us to the final and what I believe to be the correct view of postmillennialism. It encompasses all the others and yet keeps them in proper perspective. It advocates the work of the Spirit. It does not teach institutional salvation, meaning neither the civil nor ecclesiastical institutions alone can convert society. But it does not teach the work of the Spirit in converting men separate from the work of the Spirit in the transformation of their environment. Thus, covenantal postmillennialism advocates revival as well as the restoration of society.

Perhaps the best place to see this expression of covenantal postmillennialism is in two of the parables that are organized according to the pattern of the covenant. The structure of them is covenantally obvious.

- Announcement: The Suzerain Lord speaks. “Therefore He was saying” (Luke 13:18). A statement identifying the Lord’s speech is at the beginning of the Deuteronomic covenant (Deuteronomy 1:3). We see time and again that this distinguishes the Lord, making the announcement a declaration of transcendence.

- Comparison: The Suzerain Lord draws on an analogy to represent the kingdom of God. The use of representation is a matter of hierarchy. In the Deuteronomic covenant, the same covenantal principle surfaces (Deuteronomy 1 :8ff.). God chooses representatives. In the case of the mustard seed parable, God selects a mustard seed to represent the principle that He wishes to convey.

- Mechanism of Change: The Suzerain Lord equates the kingdom of God to a mustard seed that falls into the ground and grows into a tree (Luke 13:19). He presents a cause/effect principle. The seed is the mechanism of change. It refers to Jesus Himself, who is the “seed” that falls into the ground (Matthew 13). The parable therefore speaks of Christ as the personal and ethical means of transformation. He will grow the kingdom from seed to tree.

- Blessing: Inescapable to the kingdom is growth. Moreover, inescapable to the covenant blessings is also growth to the point of maturity (Deuteronomy 28:4, 12). The seed becomes a tree! There may be temporary set backs but the seed pushes its way through the ground, becoming a seedling. It fights all the elements and animals around it and pushes forward to become a small tree. It still does not stop, climbing into the sky and becoming a canopy of protection for the whole earth and a place of rest for creatures from the heaven.

- Completion: The kingdom tree becomes a resting place for the beings from heaven. The fifth segment of the Deuteronomic covenant gave instructions for entering the land of rest (Deuteronomy 30-34). The kingdom brings true sabbath rest to the world.

- Announcement: A second time the Suzerain Lord announces a parable. This is the principle of double witness, two parables bearing witness to the reality of a successful kingdom on earth.

Comparison: As before, an analogy is used to represent a certain principle of the kingdom. This time, leaven is used to picture the kingdom itself.

Mechanism of Change: The woman takes the leaven and “hides” it in “three” pecks of meal. The woman points to the image of the people of God as the bride. She hides the leaven because the assumption is that if the leaven is the kingdom then the meal in which the leaven is hidden represents the whole world. The leaven will cause the world to be raised from the dead after the third day, indicated by the “three pecks of meal” (Luke 13:21). The woman’s faithfulness causes the dominion of the Gospel, the same lesson taught in the third section of the Deuteronomic covenant (Deuteronomy 5- 26): dominion by covenantal obedience.

Blessing: The leaven leavens the whole lump. “All is leavened.” One of the blessings of the Deuteronomic covenant is, “Blessed shall be your basket and your kneading bowl” (Deuteronomy 28:5). The only way for the whole lump of dough to be leavened is for it to be “kneaded” successfully.

Completion: The implication is that the whole world is leavened and ready for baking. In other words, the kingdom covers the whole earth before Jesus returns, judges the world, bringing the heat to turn it into a meal offering before God.

In both parables we have the features of covenantal postmillennialism. God is the one who is Lord of the covenant. He appoints representatives to image His covenant with man, the kingdom. Faithful obedience is the mechanism for change, not force or coercion. Kingdom work is blessed and comes to final and complete success before the return of Christ. The operative word covenantal postmillennialism being before.

- The New Infernationa/ Dictionary of the Christian Cfrurch, J.D. Douglas, General Editor (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1974), p. 212.

- T. S. Eliot, Christianity and Culture (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1949), pp. 5-17

[source]

Then God said, “Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness; let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” So God created man in His own image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them. Then God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it; have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” -Genesis 1:26-28

And Jesus came and spoke to them, saying, “All authority has been given to Me in heaven and on earth. “Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” Amen. -Matthew 28:18-20

~