The Bible and the Land

By Rev. Dr. Munther Isaac

Introduction

The Palestinian-Israeli conflict is one of the most complex conflicts in modern history. At its core, it is a conflict about territory and control. It is a conflict about land, and not merely any land, but the biblical land. Over the years, religion has been used in this conflict by many parties to justify acts of violence and land confiscation.

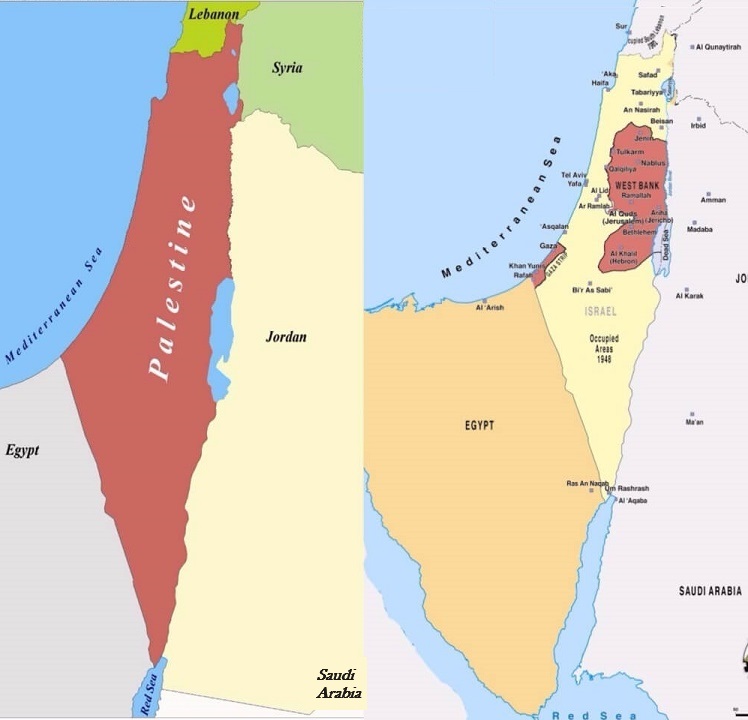

These days Jewish settlers seize control of Palestinian land by force, protected by the Israeli army, and motivated by their religious tradition. All historical Palestine,1 they argue, is “the land of Israel,” given to their ancestors (and by extension to them) as an eternal possession. All attempts by Palestinians to prove ownership of the land by legal documents or historical arguments are deemed irrelevant. When the United Nations voted unanimously against the building of Jewish settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, the Israeli ambassador to the UN responded by holding a Bible in his hand and citing thousands of years of Jewish history in the Holy Land.

On the other hand, some Palestinian fundamentalist groups also claim the whole land as waqf, a holy territory devoted to Allah. This then necessitates their action of jihad to liberate Palestine, and establish Islamic rule in it. Jerusalem, they claim, is an exclusively Islamic city.

To add up to an already complex situation where religion is used to justify a political claim, many Christian groups and churches around the world have taken sides in this conflict in the name of the Bible and the God of Bible. Many Christians believe that the biblical covenant with Abraham continues today with the Jewish people (Abraham’s physical descendants), and by extension to the State of Israel. Further, many also believe that the creation of Israel in 1948 was a fulfillment of prophecy and a sign to God’s faithfulness to the Jewish people. With regards to the land, it is assumed that God gave it to the Jewish people as an eternal possession thereby giving Jews a “divine right” to the land today.

At the same time, many Christians around the world believe that God, in the end times, will restore the Jewish people to Himself. In order for this to happen, He will first bring them to the Promised Land (which is what is happening today!), and all of this will lead to the second coming of Christ.

These are more than just theological beliefs. This is a worldview that sees the events of history as centered around Israel, the Jewish people and the land. Moreover, such beliefs today form a strong political movement often called “Christian Zionism”. Many Christians around the world are involved in political lobbying on behalf of Israel and give hundreds of millions of dollars for Israel and the building of Jewish settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem (which is illegal according international law).

Needless to say, as a Palestinian Christian, I am deeply troubled by these views. If the creation of the state of Israel is a sign of God’s faithfulness to the Jewish people, then what kind of sign is it to the Palestinian people? When the state of Israel was created, around 700,000 Palestinians became refugees and more than 500 Palestinian towns and villages were completely destroyed. How am I supposed to understand that? Furthermore, this year marks 50 years of the Israeli military occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza2. So am I supposed to believe that the state that is oppressing me and my people is in covenant with God today? And when Jewish settlers confiscate land from Palestinian farmers who have been living here for hundreds of years (if not more), are we to simply accept this because Jews have a “divine right” to “their” land and they are merely “returning” to it? Should we accept that a person who was born in Russia to a Jewish mother has more right to the land than the people who have been living here for hundreds of even thousands of years because “the Bible tells me so?”

As Palestinians, we have been totally ignored and even dehumanized in this theology. We are an afterthought. Do we matter? What is God’s plan for us? Does our existence and perspective matter?

As a Palestinian Christian, I want to ask:

What does the Bible really teach about the “Promised Land?”3

What does the Bible teach about war, conflict and peace-making?

How should Christians be involved in this conflict? What does Jesus teach about this?

Can our theology, prayers and actions serve the cause of peace, not war?

1 By historic Palestine I mean the territory that was under British mandate before 1948.

2 This is the territory over which Palestinian leaders today are seeking to establish a Palestinian state – also known as the 1967 borders.

3 Actually, I wrote my PhD thesis on this question and it is now published in a book!

1 - Whose Land is it Anyway?

When it comes to the question of “the Bible and the land,” we must begin with the question: “Whose land is it?” This is a simple yet immensely significant question. You get this wrong, and you get the rest of the story wrong. And the good news is that you don’t need a PhD to get this right! Are you ready for it?

THE LAND BELONGS TO GOD. PERIOD.

The Bible is clear that the whole earth was created by God and belongs to Him. “The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof, the world and those who dwell therein” (Ps. 24:1; see also Deut. 14:10). What the Bible teaches about creation is foundational for our discussion on the theology of the land. God created this earth and appointed Adam as His representative on it, and Adam was assigned as God’s vicegerent. As humans, we are stewards of God, and He holds us accountable for our actions with regards to His creation. The earth – God’s earth – is humanity’s mandate:

“And God blessed them. And God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.’ ” (Gen. 1:28)

This concept of the creation mandate is the same one reflected in Israel’s theology of the land. When God gave biblical Israel the land, in accordance to the promises to their forefathers, He made it clear that the land will remain His land regardless:

“The land shall not be sold in perpetuity, for the land is mine. For you are strangers and sojourners with me.” (Lev. 25:23)

“The land is mine,” says God. The land belongs to God. It was His land. It is His land. It remains His land.

This verse comes in the context of the Jubilee laws in the book of Leviticus. The importance of these laws is that they are a reminder to biblical Israel that she does not own the land, for the land belongs ultimately to God. Biblical Israel is not free to do with the land whatever she wants, or to claim eternal possession of it. These laws are a reminder that “land is not from Israel but is a gift to Israel, and that the land is not fully given over to Israel’s self-indulgence.”1

“Like all tenants, therefore, Israelites were accountable to their divine landlord for proper treatment of what was ultimately His property.”2

Such a way of administrating the land in the Bible was a challenge to the concept of empire, where the king owned and administrated the land, and the people were mere servants or slaves (1 Sam. 8:10-17). Here we are reminded that God is the ultimate king.

This is also a reminder to us today that we possess nothing. We think we do, but in fact, everything we own or possess ultimately belongs to God. We are God’s stewards on earth.

Once we establish this crucial foundational point, then – and only then – we can move forward with the study of the land in the Bible. The land belongs to God. Amen.

1 Brueggemann, Walter, 2002, The Land: Place as Gift, Promise, and Challenge in Biblical Faith, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, p. 59.

2 C.J.H. Wright, 2004, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God, Inter-Varsity Press, Illinois, p. 94.

2 - What Were the Boundaries of the Promised Land?

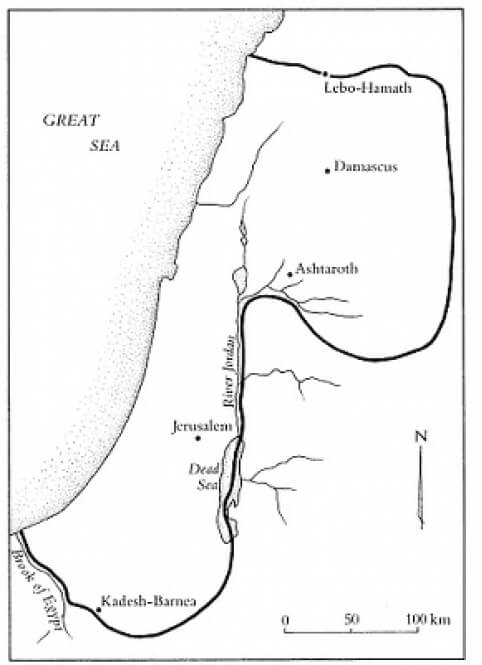

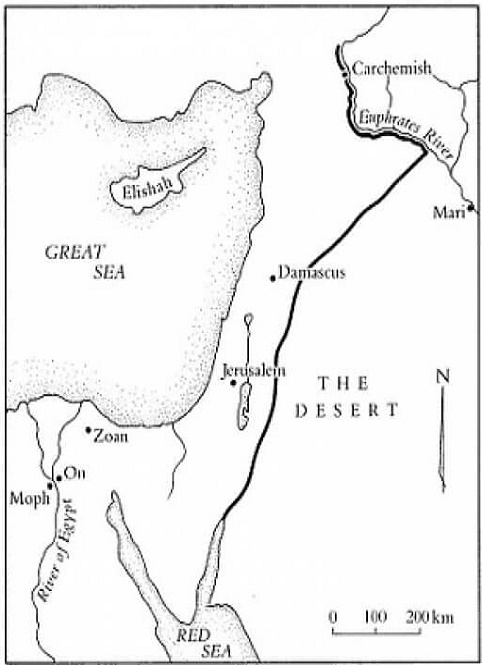

Many Bible-believing Christians assume that the modern region known as Israel and Palestine reflects the actual boundaries of the biblical Promised Land. But is that true? What were the boundaries of the Promised Land? The issue is controversial because of the different descriptions that we find in the Bible of these boundaries.1 The Bible does not give just one description of the boundaries. It is not that simple.

But let me try to simplify things, by dividing these different boundary descriptions into roughly two maps: (1) the land of Canaan, (see map 1 below) and (2) a wider territory (from river to river) that includes most of the Ancient Near East (see map 2 below). In addition, in the different periods, the land had different shapes. The allotted land in the days of Joshua, for example, is different from the land during the reign of David and then Solomon. In both cases, the boundaries went beyond modern day Israel and Palestine.

Map 1: Numbers 34.3-12. Map 2: Genesis 15:18-21.

Source: M. Weinfeld, 2003, The Promise of the Land: The Inheritance of the Land of Canaan by the Israelites,University of California Press, Berkeley, pp. 57-58

The promise to Abraham in Genesis 15 is most striking to us:

On that day the LORD made a covenant with Abram, saying, “To your offspring I give this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates, the land of the Kenites, the Kenizzites, the Kadmonites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Rephaim, the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Girgashites and the Jebusites.” (Gen. 15:18-21)

I would like to pause and suggest to our Christian Zionist friends that if they insist on using the Bible to justify Jewish sovereignty over modern day Palestine and Israel, then they should also call for Israel to invade Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. That is, if they wish to be consistent, or, simply just stop using the Bible!

In all seriousness though, what did these boundaries reflect? According to Jewish scholar Wazana, using water boundaries in the Ancient Near East had significant indications:

The promise reflected in spatial merisms is not to be understood literally, nor should it be translated and transformed into border lines on maps. It is a promise of world dominion. The spatial merisms in promise terminology reflect a land that has no borders at all, only ever-expanding frontiers; they are referring to universal rule.2

Similarly, Palestinian theologian Yohanna Katanacho argues that “it seems that the land of Abraham is not going to have fixed borders. It will continue to expand, thus increasing in size both territorially and demographically. The land of Abraham will continue to extend until it is equal to the whole earth”.3

Moreover, in many Messianic prophecies we see what we can describe as the “Messianic Land”. For example, Psalm 2:8 declares that God will give the King the nations as His inheritance, and the ends of the earth as his possession (Ps. 2:8; see also Ps. 72: 8, 11). Micah 5:4 says that the ruler of Bethlehem “shall be great to the ends of the earth,” and Zechariah 9:10 speaks of the coming King that “His rule shall be from sea to sea, and from the River to the ends of the earth”. Finally, Isaiah 54:2-4 speaks clearly about the expansion of Jerusalem in the eschaton.

In short, the theology of the land has a universal dimension. We cannot simply speak about the theology of the land, but we should speak instead about the theology of the earth. The land, according to this biblical belief, is indeed the whole earth. The theology of the land is ultimately the theology of the earth, and this, in turn, will take us back to the creation (Ps. 24:1).

We should not then be surprised when we read in Romans 4:13 that Abraham was promised that he will inherit “the world” (not merely the land!). Nor should we be surprised when Jesus declared before his ascension that all authority “in heaven and on earth” has been given to Him.

God is not merely concerned with a small piece of land in the Ancient Near East. He is the God of all peoples and all lands. Canaan was only the first stage – not the goal.

1 Gen. 12:5; 17:8; 15:18-21; Ex. 23:31; Num. 34:1-12; Deut. 1:7; 11:24; Josh. 1:3-4; Judg. 20:1; 1 Sam. 3:20; 2 Sam. 3:10; 17:11; 24:2, 15; 1 Kgs. 4:25m; 10:23-24.

2 N. Wazana, 2003, From Dan to Beer-Sheba and from the Wilderness to the Sea: Literal and Literary Images of the Promised Land in the Bible, in M.N. MacDonald (ed), Experiences of place, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass, p. 71.

3 Y. Katanacho, 2012, The Land of Christ, Bethlehem Bible College, Bethlehem, p. 80.

3 - The Land and the Covenant

The Land and the Covenant

Whenever I am in a debate or discussion on the theology of the land, I almost always get the question: “But aren’t the promises of land eternal and unconditional?” This is an assumption shared by many Christians, but usually without considering the full consequences of such a statement. If this is true, then it means no matter what biblical Israel did, she and her ancestors will always be the legitimate owners of the land.

Now, I have a serious problem with this line of thinking, for it makes God unconcerned with our faithfulness and our responsibility to our neighbor or to the land itself. There is no accountability. So, we must ask, is this thinking biblical to begin with? I would like to suggest that the answer is “no”. This line of thinking also ignores the wider framework of the theology of the land in the Old Testament, namely the covenant. As Chris Wright says:

It is insufficient simply to say that the LORD ‘gave the land to Israel’, without taking into consideration the context of the gift, which was the covenant relationship and its reciprocal commitments. The land was an integral part not only of the LORD’s faithfulness to Israel, but also of Israel’s covenantal obligation to the LORD.1

In the discussion about the land in the Old Testament, we must ask, “Did God give the land to Israel without any conditions, or were the promises really unconditional?

For this, we need to begin at the first calling to Abraham (Gen. 12:1-3). There, the more accurate translation of verse two should read as: “Be a blessing so that I can bless those who bless you”. In other words, there is an element of conditionality in the first call to Abraham. The evidence from the translation of the Hebrew text of Gen.12:2b is indeed a strong one, and is supported by the larger Abrahamic narrative. The covenant of Gen. 15:17-18 is preceded by a reference to Abraham’s faith (15:6): “And he (Abraham) believed the LORD, and he counted it to him as righteousness”. The narrative in Gen. 17 starts with a call for Abraham to walk before God and be perfect (17:1), and ends with a commandment of circumcision (17:9-10). Gen. 18:19 makes justice a condition to the fulfilment of the promise, and Gen. 22 makes the point that it is because Abraham obeyed that he will receive the blessing, including the land.

When we move forward in the story to Israel’s time before they entered the land, we see clearly that the status of Israel in the land was conditional to obedience:

Do not make yourselves unclean by any of these things, for by all these the nations I am driving out before you have become unclean, and the land became unclean, so that I punished its iniquity, and the land vomited out its inhabitants. But you shall keep my statutes and my rules and do none of these abominations, either the native or the stranger who sojourns among you (for the people of the land, who were before you, did all of these abominations, so that the land became unclean), lest the land vomit you out when you make it unclean, as it vomited out the nation that was before you.” (Lev. 18:24-28)

(Apologies for the strong and vivid language. It’s the Bible!)

The warnings in these verses are strong and clear. The land does not tolerate ungodliness. Holiness is a requirement to dwelling in the land. In fact, the text equates Israel with the nations that dwelt in the land before her. Israel is no better than those nations. She will not hold any special status in the land. If anything, she is held to higher standards, since she was given the law. There is no “free gift” here with “no strings attached”.

Bible scholars usually observe three areas that Israel had to observe if she was to stay in covenant with God. The first is idolatry. Worshiping other gods will cause Israel to forfeit its right to stay in the land. The second are Sabbath and Jubilee laws. The third is justice. And guess which of these sins is tied more directly with being expelled from the land? Indeed, it is the sin of socio-economic injustice. Let us consider some references:

Justice, and only justice, you shall follow, that you may live and inherit the land that the LORD your God is giving you. (Deut. 16:20)

Jeremiah makes a similar point:

For if you truly amend your ways and your deeds, if you truly execute justice one with another, if you do not oppress the sojourner, the fatherless, or the widow, or shed innocent blood in this place, and if you do not go after other gods to your own harm, then I will let you dwell in this place, in the land that I gave of old to your fathers forever (Jer. 7:5-7).2

These social justice laws are so important for our understanding of the theology of the land. The land was supposed to be a place of equality and justice, and where the powerless are protected.

The same applied to post-exile Israel. For example, Ezekiel 33:24-26 gives a strong warning against relying on ethnicity or the past to possess the land again:

Son of man, the inhabitants of these waste places in the land of Israel keep saying, ‘Abraham was only one man, yet he got possession of the land; but we are many; the land is surely given us to possess.’ Therefore say to them, ‘Thus says the Lord GOD: You eat flesh with the blood and lift up your eyes to your idols and shed blood; shall you then possess the land? You rely on the sword, you commit abominations, and each of you defiles his neighbor’s wife; shall you then possess the land?’ (Ezek. 33:24-26)

It is amazing how relevant these verses are for today, where we see many who “rely on the sword” and on being children of Abraham in the flesh. “Shall you then possess the land?”

Even after the exile, dwelling in the land was conditional to obedience. In short, there is no “cheap grace” in the Bible. God holds all those who receive his gifts accountable before him. We saw this with Adam and Eve, and now we see it with Israel. With election comes responsibility. Just like Adam and Eve lost Eden because of disobedience, Israel lost the land because of disobedience.

1 C.J.H. Wright, 2004, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God, Inter-Varsity Press, Illinois, p. 92.

2 See also Jer. 7:8-15; 21:12-14; 22:3-5; Isa. 5:12-13; Ezek. 16:49.

4 - Eternal Possession?

Eternal Possession?

When the Bible claims that something is to last forever, then surely this means it will last forever, right? Any Bible-believing Christian who reads the Bible literally must know so. But is it so? Does “forever” in the Bible always mean forever? As in never-ending?

One example from the Old Testament is sufficient to show that “forever” does not always indicate unconditionality. Let us look at 1 Samuel 2:30:

Therefore the LORD, the God of Israel, declares [to Eli]: “I promised that your house and the house of your father should go in and out before me forever,” but now the LORD declares: “Far be it from me, for those who honour me I will honour, and those who despise me shall be lightly esteemed”.

In this verse, God makes a promise of eternal priesthood to Eli, using the term “forever”, but then surprisingly revokes this eternal promise almost immediately. This verse and other promises in the OT show that eternal promises can be “revoked” by God.1 Chris Wright suggests therefore that the expression “forever” in the OT “needs to be seen, not so much in terms of ‘everlastingness’ in linear time, but rather as an intensive expression within the terms, conditions and context of the promise concerned”.2 (I hope this did not shake your faith!)

What about the term “inheritance”? What does it mean that biblical Israel received the land as an inheritance? Clearly, it does not mean that God died and left the land as a possession to his children Israel. Biblical scholars can help us here. Rendtorff suggests that “inheritance” is “God’s possession, which is handed over and left to Israel as a possession given on trust, as it were as a ‘fief’”.3

It is important, therefore, to emphasize that the gifted land is always a covenanted land under treaty. It is therefore better, and more in line with the biblical narrative, to define “inheritance” as a mandated land. In the words of Brueggemann:

Land with Yahweh brings responsibility. The same land that is gift freely given is task sharply put. Landed Israel is under mandate.4

Chris Wright also uses a very helpful analogy to describe biblical Israel’s relationship with God and the land, and he derives it from Lev. 25:23. For him, God is the divine “landlord”, and the Israelites are his tenants. They “possess” the land. They “occupy” and use it. But God “owns” the land. He concludes:

Like all tenants, therefore, Israelites were accountable to their divine landlord for proper treatment of what was ultimately his property.5

The land was given to biblical Israel as a gift, but that did not make it her property. The land was not simply an arbitrary gift for Israel’s enjoyment, but rather a mandate that comes with responsibility. This is the reason why Israel was brought into a land in the first place. Palestinian theologian Tarazi thus reads the allotment of the land not as an allocation of land to each of the tribes, as though each would become owner. Rather, the allotment was an assigning of the tribes to certain parts of the land.6 In other words, in the land, Israel is given a mandate – a responsibility and a task. It is not the other way around. Israel is assigned to the land, and not the land to Israel. This may then explain why the Levites were not assigned land, because they already had a task or mandate:

Therefore, Levi has no portion or “inheritance” with his brothers. The LORD is his “inheritance”, as the LORD your God said to him (Deut. 10:9).

The inheritance of the tribe of Levi is God and this means that serving him is their assignment. Similarly, the rest of the tribes have a different portion and a different assignment. The tribe of Levi serves the Lord in the sanctuary, just as the Israelites serve the Lord in the land. It is not so much about territory. It is about service.

Therefore, the concept of “inheritance” does not and cannot mean “possession”. A better understanding for inheritance within the bigger biblical picture is “mandate” or “task”.

May I remind us that in the end that we “possess” nothing. Everything we have today belongs to God. We are but stewards, and our homes, neighborhoods and lands are ultimately God’s. “The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof, the world and those who dwell therein.” (Ps. 24:1).

1 Other examples that illustrate this use of forever are Ex. 29:9; Jer. 35:19; Num. 25:10-13; 1 Sam. 2:30; 1 Chr. 23:13.

2 C.J.H. Wright, 1992, A Christian Approach To Old Testament Prophecy Concerning Israel, in Walker (ed), Jerusalem Past and Present in the Purposes of God, Tyndale House, Cambridge, p. 6.

3 R. Rendtorff, 2005, The Canonical Hebrew Bible: A Theology of the Old Testament, Deo, Leiden, p. 460 (emphasis added).

4 Brueggemann, Walter, 2002, The Land: Place as Gift, Promise, and Challenge in Biblical Faith, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, p. 94.

5 C.J.H. Wright, 2004, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God, Inter-Varsity Press, Illinois, 2004, p. 94 (emphasis added). Cohn also uses the same terminology of Israel as tenants. R. Cohn, 1990, From Homeland to the Holy Land: The Territoriality of Torah, Continuum, 1(1), p. 6.

6 P.N. Tarazi, 2009, Land and Covenant, Ocabs Press, St. Paul, Minnesota, p. 130

5 - The Land and Justice

Justice matters to God! I am amazed how often this concept is missing in many Christian theology and mission books. It is missing from the teaching and preaching of the church, and this is indeed sad!

The Bible speaks a lot about justice. I mean a lot. And the theology of the land is a good place to start. No other sin in the OT was tied more directly with being expelled from the land than the sin of socio-economic injustice. Justice is emphasized in almost all the traditions. In Genesis 18:19, God says about Abraham:

For I have chosen him, that he may command his children and his household after him to keep the way of the LORD by doing righteousness and justice, so that the LORD may bring to Abraham what he has promised him.

Abraham was chosen for this reason: doing righteousness and justice, and this would bring the promise to fulfilment. In Deut. 16:19-20, justice is again portrayed as a prerequisite to staying in the land:

You shall not pervert justice… Justice, and only justice, you shall follow, that you may live and inherit the land that the LORD your God is giving you.

The first five books in the Bible have a lot to say about the poor, the stranger, the sojourner, the widow, and orphan.1 They are redefined, according to Brueggemann, as “brothers and sisters”. “It is one of the tasks that goes with covenanted land and keeps the land as covenanted reality: those who seem to have no claim must be honored and cared for”.2 This is because land is not “for self-security but for the brother and sister”.3

Yet it was the “classical” prophets who elevated this issue above probably all other considerations and related it directly to the exile. As Chris Wright says, “The prophets simply would not allow Israel to get away with claiming the blessing and protection of the covenant relationship for their society while trampling on the socio-economic demands of that relationship.”4

Amos is noticeable for his emphasizing social justice. His call to “let justice roll down like waters” (5:24) is followed by a warning of exile; “and I will send you into exile beyond Damascus” (5:27).5 Jeremiah makes a similar point:

For if you truly amend your ways and your deeds, if you truly execute justice one with another, if you do not oppress the sojourner, the fatherless, or the widow, or shed innocent blood in this place, and if you do not go after other gods to your own harm, then I will let you dwell in this place, in the land that I gave of old to your fathers forever (Jer. 7:5-7).6

Jeremiah compared in chapter twenty-two the reigns of two kings of Israel: Josiah, who was just, and Jehoiakim, who abused his power. For Jeremiah, the overall wellness of the kingdom has to do with justice. If there is justice, all will go well. “Joshiah,”declared Jeremiah, “judged the cause of the poor and needy; then it was well.” Then he adds something extremely important: “Is not this to know me?” (22:16)

Did you get this? Knowing God and doing justice are the same thing! They are inherently related. You cannot claim to know God while not caring for the poor! It is that simple! This is why in Jeremiah 9:23-24 we read:

“Thus says the Lord: “Let not the wise man boast in his wisdom, let not the mighty man boast in his might, let not the rich man boast in his riches, 24 but let him who boasts boast in this, that he understands and knows me, that I am the Lord who practices steadfast love, justice, and righteousness in the earth. For in these things I delight, declares the Lord.”

Again, knowing God and having a conscience for justice cannot be separated! It is that simple. (How in many systematic theology books mention justice as a character of God in addition to omnipresence and omnipotence, etc.?)

Justice matters! It matters to God! It mattered in biblical times and it matters today. It is in fact a central theme in the Bible. Yet sadly, and in a strange way, justice is a missing component from the mission, teaching, theology and ministry of most churches and mission agencies. It is time to pause and ask deep and serious questions about how we understand the Bible and mission, and why we have ignored justice!

1 See for example Ex. 22:21-24, 23:6, 9; Deut. 10:19; 15:7-11; 24:19-22.

2 Brueggemann, Walter, 2002, The Land: Place as Gift, Promise, and Challenge in Biblical Faith, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, p. 61.

3 Ibid., p. 73.

4 C.J.H. Wright, 2004, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God, Inter-Varsity Press, Illinois, 2004, p. 98

5 See also Amos 6:6-7.

6 See also Jer. 7:8-15; 21:12-14; 22:3-5; Isa. 5:12-13; Ezek. 16:49.

6 - Land Confiscation

Imagine working hard for years and saving money to purchase a piece of land to secure your future and the future of your children, only for an occupying army to arrive in this land and confiscate it by force for the use of the “empire”. In Palestine, this is not imagination. This is reality under occupation.1

Land confiscation is not a new phenomenon in this land. In the biblical tradition, perhaps no other story illustrates this abuse of power by the “king” with regards to the land than the story of king Ahab and the vineyard of Naboth (1 Kings 21). The relatively large space this narrative received in the book of Kings is an indication that the narrative demands special attention. Ahab, king of the northern kingdom, saw the vineyard of Naboth the Jezreelite, coveted it, and presumed that he had divine entitlement to ask Naboth to sell it to him (21:2). Naboth, on the other hand, rejected this based on his belief that this is a land entrusted to him by God as an inheritance, and therefore he could not sell it (21:3).

The infamous queen Jezebel intervened in the story, and reminded Ahab that, as king of Israel, he was entitled to take the vineyard (21:7). The assumption is simple: “Just because you can, then you should!” A plot was made, Naboth was killed, and Ahab received the vineyard (21:16). No apology was made. Power and manipulation were at play here. The victim in this narrative was Naboth, who represents the powerless peasants of Israel. The way in which Naboth and Ahab related to the land manifested a startling contradiction. One treated it as a gift, the other as an entitlement. One believed that it belonged to the community; the other wanted it for his empire.

The attitude of Naboth is similar to that of many contemporary Palestinian farmers. It is no surprise that Palestinians take the olive tree as a symbol, for it reminds them of their rootedness and belonging to the land. This attitude can be summarized by the words of Brueggemann:

Naboth is responsible for the land, but is not in control over it. It is the case not that the land belongs to him but that he belongs to the land.2

The Bible is a book of hope and justice, and that was not the end of the story. The story concluded with judgment on Ahab. He was found guilty for murder and “taking possession:”

“Thus says the Lord: Have you killed and also taken possession? … In the place where dogs licked up the blood of Naboth shall dogs lick your own blood”. (1 Kings 21:19)

The king, who was supposed to be the guardian of justice in the land (Psalm 72), instead was responsible for inflicting injustice on the people of the land. God intervened and brought justice, for he is a God who is concerned for justice. Ahab had forgotten that:

“Justice, and only justice, you shall follow, that you may live and inherit the land that the LORD your God is giving you”. (Deuteronomy 16:20)

Interestingly, justice took place in the same place where Naboth was killed, hinting maybe that the land avenged the death of Naboth. God is a God of justice, and this our biblical hope.

Let us remember that our biblical hope was revealed in the child of Bethlehem, who promoted and incarnated a new way of kingship. Jesus is the ultimate just and humble king. Of him the prophet Jeremiah said:

“Behold, the days are coming, declares the LORD, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he shall reign as king and deal wisely, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the land”. (Jeremiah 23:5)

As his followers today, Jesus invites us to promote his kingdom and his vision for the land. The righteous king of Bethlehem rules with justice and righteousness, and so justice and righteousness should characterize our ministry.

1 See for the example the case of Cremisan: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/10/palestinians-mourn-final-cremisan-valley-olive-harvest-161031094433899.html.

2 Brueggemann, 2002, p. 88.

7 - Who is Israel in the Bible?

Many Christians simply assume that the modern state of Israel is a direct continuation of the Israel of the Bible, and that the Jews of today are the direct descendants of Abraham. As such, the Abrahamic covenant, which included the promise of the land, is still valid and applies to modern Israel. Furthermore, the promise in Gen. 12:1-3 that God will bless those who bless Abraham and curse those who curse Abraham is transferred today to modern Israel: those who bless the state Israel are blessed and those who oppose the state of Israel are cursed.

I would like here to only challenge the premise that membership in Israel in the OT is entirely dependent on race. In other words, is the Israel of the Bible an entity defined exclusively by race? Now we need to be careful before we answer this question; answering with a “yes” would mean that God is racist!

When we read the biblical history, it will become apparent that the biblical narrative is almost exclusively focused of what one might call the “holy seed” – the seed chosen by God for the redemption of the world. This is the seed of Abraham which became the people Israel. Yet when we read the story carefully, we realize that one can be born in the family of Israel yet not considered part of the seed. This is evident in the examples of Ishmael and Esau for example. And this was captured by Paul in his letter to the Romans:

For not all who are descended from Israel belong to Israel, and not all are children of Abraham because they are his offspring (Rom. 9:6-7)

Moreover, there are those who were born outside of the family, yet were considered part of Israel. Ruth, the Moabite, is the obvious example. She declared to Naomi her mother in law that “Your people shall be my people, and your God my God” (Ruth 1:16). As such,

The Book of Ruth illustrates that the benefits of the God’s covenant are not limited by any boundaries, whether national, rational, or gender. Ruth is constantly referred to as the Moabite. Her ethnic and national background is not forgotten in the book, which teaches that even this Moabites woman can live in covenant with YHWH and benefit from faithful relationship with Him.1

Think with for a moment: if Ruth the Moabite believed in the God of Israel and was considered as a result part of Israel, don’t all Christians today believe in the God of Israel?

Moreover, the bible is full of inter-marriage. Judah married a Canaanite, Joseph an Egyptian, Moses a Medianite, and Solomon many foreign women. Not only that, but we read in Judges:

So the people of Israel lived among the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites. And their daughters they took to themselves for wives, and their own daughters they gave to their sons, and they served their gods. (Judges 3:5-6)

And what about the nations who became Jews during the Persian times:

And many from the peoples of the country declared themselves Jews, for fear of the Jews had fallen on them. (Est 8:17)

These people who converted to Judaism, or who became part of Israel though intermarriage – does this mean that they inherit the land?! So, is it by ethnicity? Or by faith?!

In other words, Israel, in the OT at least, is not exclusively a matter of DNA. Faith and divine election, are also factors. This becomes crucial when we consider the testimony of the NT on “who is Israel?” or “the seed of Abraham”. If someone can join Israel by faith, then this must have crucial consequences for our discussion on the land. In addition, and based on the testimony of the OT, we must ask: Can anybody claim a pure DNA from Abraham to today— and then claim possession of the land!?

1 B. T. Arnold & B/ E. Beyer, 1999, Encountering the Old Testament. Baker Books, Grand Rapids, MI., p. 193.

8 - Why a Land?

Have you ever asked yourself: “Why did God promised Abraham and his descendants a land, to begin with?” Really, think with me: why didn’t God simply tell Abraham to wonder around in the universe and preach the message of the living God? Why was the land necessary?

To answer this question, we suggest that we start in the garden of Eden and the fall and expulsion from Eden, and read the election of Abraham and the assignment of land to his seed in as restoring humanity back to Eden. As Hamilton observes:

The blessing of Abraham promised seed, land, and blessing. The promise of seed overcomes the cursed difficulty of childbearing and the loss of harmony between the man and the woman. The promise of land hints at a place where God will once again dwell with his people. The promise of blessing heralds the triumph of the seed of the woman over the seed of the serpent.

Looking at the land from this perspective, we can conclude that the land promise is not an end in itself, but rather the first step of an answer to a universal and human problem. Israel is not promised and given the land for her sake or for the sake of receiving a land. Israel is chosen and given a land so that she becomes “the vehicle by which the blessing of redemption would eventually embrace the rest of humanity”. Through Abraham and the newly established community, and from this newly Promised Land, the families of the earth are to be blessed, and Abraham will eventually become the “father of many nations”.

We should also notice the pattern that is echoed in OT biblical theology – that of a blessed humanity filling the earth. According to the biblical canon, God’s first communication with humanity included a blessing followed by a commandment:

And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion…” (Gen. 1:28)

This calling is precisely what is echoed in God’s calling of Abraham– something which we might fail to see if we start the biblical theology of the land in Gen. 12. To be sure, Israel may have started in Gen. 12, but she remains only one ingredient of the Bible’s overarching story. The biblical story starts before Israel, and will go on after and beyond Israel. The biblical hope for the redemption of Israel and her land is ultimately a biblical hope for the redemption of the world and its nations.

In addition, the giving of a land as part of this project of redemption highlights that God is committed to his created order and to the redemption of human society. Redemption in the OT is not merely about individuals, personal piety, or spiritual existential experiences. It is about redeeming whole societies on earth, and ultimately the whole of humanity. It is an “earthly” phenomenon.

Indeed, the biblical storyline could have been different: God could have given Abraham moral commandments for himself and his family. He could have instructed him to wander around in the world proclaiming the worship of the one true God. Instead, he chooses to bring Abraham to a place, to engage in human history and geography, and to create from Abraham’s descendants a unique and distinct society – one that would reflect his image on earth in the midst of the nations. This is the biblical pattern of redemption.

All of this then pushes us to the conclusion that the theology of the land, following the pattern of Eden, is not about a small piece of real estate in the ANE or about the small ethnic group that inherited it. The land is part of a larger scheme that is about redeeming and restoring the whole of creation. The restoration of the whole earth starts with one particular land and one family.

Moreover, Israel was supposed to be an ideal community in the midst of the nations (Ex. 19:5). As such, the regulations and laws about the land in Israelite society can be viewed as a model for the ideal in ancient times. Chris Wright calls this “a paradigmatic understanding” of the relevance of OT Israel to other nations in other lands. Wright’s book Old Testament Ethics for the People of God explores some of the land laws in the OT in detail, and their relevance for today’s world. He argues:

Many of the OT laws and institutions of land use indicate an overriding concern to preserve this comparative equality of families on the land. So the economic system also was geared institutionally and in principle towards the preservation of a broadly based equality and self-sufficiency of families on the land, and to the protection of the weakest, the poorest and the threatened – and not to interests of wealthy, landowning elite minority.

Wright observes for example how in the Canaanite society the king owned all the land and there were feudal arrangements with those who lived and worked on it as tax-paying tenant peasants. Meanwhile, the land in Israel was divided up as widely as possible into multiple-ownership by extended families. In other words, Israel’s way of the living in the land was supposed to be an example and a challenge for other nations in other lands.

Finally, this pattern of choosing a nation and a land and dwelling in the midst of people underscores God’s desire for fellowship with humanity. The OT portrays God as a God who seeks to dwell among humanity. This is evident throughout the OT biblical history, whether in the Garden of Eden, the tabernacle, or the temple. It is in this sense that we could describe the faith of Israel as “incarnational”.

9 - The Land in the Old Testament: Universal and Inclusive

What is the Promised Land? Why a particular land? These are questions that we have already discussed. They led us to conclude that the Land in the Old Testament has always had a universal dimension, and points toward expansion of the land and the inclusion of new “families” and new “lands” into the family and land of biblical Israel. This inclusive nature must be rediscovered and highlighted, especially in the face of the many exclusive voices today.

Let us consider the Abrahamic covenant. From the outset, God told Abram that in him “all the families of the earth shall be blessed”. Abram’s name was changed into Abraham because God wanted to make him “the father of a multitude of nations” (Gen. 17:5). T.D. Alexander observes:

“The promise that Abraham will become a great nation, implying both numerous seed and land, must be understood as being subservient to God’s principal desire to bless all the families of the earth.”1

Moreover, in many Messianic prophecies, we see what we can describe as the “Messianic Land”. For example, Psalm 2:8 declares that God will give the king the nations as his inheritance and the ends of the earth as his possession (Ps. 2:8; see also Ps. 72: 8, 11). Micah 5:4 says that the ruler of Bethlehem “shall be great to the ends of the earth”, and Zechariah 9:10 speaks of the coming king that “his rule shall be from sea to sea, and from the River to the ends of the earth”. Finally, Isaiah 54:2-4 speaks clearly about the expansion of Jerusalem in the eschaton.

Psalm 87 is very striking in its inclusivity. It speaks of a day when Jerusalem will be a multinational city:

On the holy mount stands the city he founded; the Lord loves the gates of Zion more than all the dwelling places of Jacob. Glorious things of you are spoken, O city of God. Selah

Among those who know me I mention Rahab and Babylon; behold, Philistia and Tyre, with Cush— “This one was born there,” they say. And of Zion it shall be said, “This one and that one were born in her”; for the Most High himself will establish her. The Lord records as he registers the peoples, “This one was born there.” Selah

Yohanna Katanacho comments on this Psalm:

“Psalm 87 puts a vision of equality and an absence of subordination before us. There are no second-class citizens in Zion. This equality is not just civic but is also covenantal. They all share the same God, are born in the same city, and registered by the same hands. Their linguistic, historical, and military differences are not important. What unites them is God himself. Geography is no longer a point of tension because Zion belongs to God, not Israel. It is the city of God, and he alone can grant citizenship in his city. Citizenship comes by divine declaration, not by biological rights.”2

Another striking statement that speaks of the inclusive nature of Israel in the coming age is the one by Ezekiel towards the end of his book, when he says that sojourners shall be allotted an inheritance among the Israelites:

So you shall divide this land among you according to the tribes of Israel. You shall allot it as an inheritance for yourselves and for the sojourners who reside among you and have had children among you. They shall be to you as native-born children of Israel. With you they shall be allotted an inheritance among the tribes of Israel. In whatever tribe the sojourner resides, there you shall assign him his inheritance, declares the Lord God. (Ezek. 47: 21-23)

Ezekiel seems here to reflect a tension in post-exilic Israel as it pertains to attitudes towards foreigners. Ezek. 44:5-9, in a manner similar to what we find in Ezra-Nehemiah, advocates an exclusive theology in an attempt to preserve the identity and purity of Israel. Ezek. 47:20-23, on the other hand, anticipates a time – in the coming age – in which a transformed and secure Israel will incorporate non-Israelites and allow them to have even an inheritance in the land.

The book of Isaiah also has a strong positive and inclusive attitude towards the nations. The Zion we find there will be inclusive of other ethnicities and nationalities, and the words of God will guide all the nations (Isa. 2:2-3). One of the clearest statements in Isaiah that shows a remarkably positive attitude towards the nations as it pertains to the temple is found in Isaiah 56. There, Isaiah claims that one day the temple will be a “house of prayer for all peoples”. In the new temple, everybody will be equal, reminiscent of the original state of humanity:

Let not the foreigner who has joined himself to the LORD say, “The LORD will surely separate me from his people” and let not the eunuch say, “Behold, I am a dry tree.” For thus says the LORD… I will give them an everlasting name that shall not be cut off. And the foreigners who join themselves to the LORD, to minister to him, to love the name of the LORD, and to be his servants… these I will bring to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer; their burnt offerings and their sacrifices will be accepted on my altar; for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples”. (Isa. 56:3-7)

Isaiah’s remarkable vision of a universal Zion and his statement that the temple will be called a house of prayer for all peoples, in addition to Ezekiel’s words about the equal status of the sojourners and their sharing of the inheritance reveal a voice within the OT tradition that hopes for a future in which Jerusalem, the temple, and the land will be inclusive and open to all.

We can thus conclude that the OT advocates for a vision in which the land becomes both universal and inclusive. One place for all peoples; a striking contrast to our reality today.

1 T.D. Alexander, 2002, From Paradise to the Promised Land: An Introduction to the Pentateuch, Paternoster Press, Cumbria, p. 146 (emphasis added).

2 Y. Katanacho, 2012, Jerusalem is the City of God: A Palestinian Reading of Psalm 87, in S. Munayer & L. Loden (eds), The Land Cries Out. Theology of the Land in the Israeli-Palestinian Context, Wipf and Stock, Eugene, OR, p. 196.

10 - The New Testament and the Land

A Christian theology of the land must ask: How did the New Testament read the Old Testament? This is indeed a very important question when it comes to a Christian theology of the land. As a Palestinian Christian, I am dumbfounded by how many Christians read the promises of the land to Israel as if Jesus never came. Jesus is not only the center of our faith, but the point towards which the OT narrative has been going all along.

The place to start our investigation of the land theme in the NT, therefore, is the life of Jesus. “No biblical theology of the land is possible which bypasses Jesus on this issue”.1 It is of great significance that all four Gospels start their narrative of Jesus by linking him with the OT narrative, and by arguing that Jesus is in fact continuing this narrative. Matthew’s genealogy (1:1-17), Mark’s citation of Isaiah and Malachi (1:2-3), Luke’s account of the words of the angel and the prayers of Mary and Zechariah (1:16-17, 46-55, 68-79), and John’s claim that Jesus came to his “own” (1:11) – all point to the conclusion that the evangelists saw the “Jesus-event” that they are narrating as the continuation and the climax of the story of Israel. As Dunn confirms:

“Unless a NT theology both recognizes and brings out the degree to which the NT writers saw themselves as in continuity with the revelation of the OT and as at least in some measure continuing or completing that revelation, it can hardly provide a faithful representation of what they understood themselves to be about.”2

The belief that the Jesus-event is the climax of the story of Israel is evident in Luke’s account of Jesus’ post-resurrection words to his disciples that everything written about him in “the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms” must be fulfilled: his suffering, resurrection, and the proclamation of the Gospel to the nations beginning from Jerusalem (Lk. 24:44-47). And as Enns comments:

“Jesus is not saying that there are some interesting Old Testament prophecies that speak of him… Rather, he is saying that all Scriptures speak of him in the sense that he is the climax of Israel’s story. The Old Testament as a whole is about him, not a subliminal prophecy or a couple of lines tucked away in a minor prophet. Rather, Christ—who he is and what he did—is where the Old Testament has been leading all along.”3

In addition, N.T. Wright points out that it was Jesus himself, and not simply the NT writers, who communicated this impression:

“Jesus… claimed in word and deed that the traditional expectation was now being fulfilled. The new exodus was under way: Israel was now at last returning from her long exile. All this was happening in and through his own work.”4

One of the most importance statements of Paul in this regard is 2 Cor. 1:20: “For all the promises of God find their yes in him”. This is “one of the most theologically pregnant statements in all of Paul’s writings”.5 Moreover, Walker argues that the phrase “all the promises” would necessarily include those concerning the land.6 In other words, the story of Israel, in its totality, including the part related to the land, must find its fulfilment – its yes – in Jesus. The place to start our investigation of the land theme in the NT, therefore, is the life of Jesus.

And this is why Palestinian theologians insist that we must read the OT prophecies through the lens of the New Testament. The coming of Jesus brings new meaning and new insights to the story and theology of Israel:

We, Christian Palestinians, believe, like all Christians throughout the world, that Jesus Christ came in order to fulfill the Law and the Prophets. He is the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end, and in his light and with the guidance of the Holy Spirit, we read the Holy Scriptures. We meditate upon and interpret Scripture just as Jesus Christ did with the two disciples on their way to Emmaus. As it is written in the Gospel according to Saint Luke: “Then beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them the things about himself in all the scriptures” (Lk. 24:27)7

1 Walker, Peter. “The Land in the Apostles’ Writings.” In The Land of Promise. Edited by Philip Johnston and Peter Walker. Illinois: Apollos Intervasity Press, 2000, p. 115.

2 J.D.G. Dunn, 2009, New Testament Theology: An Introduction, Abingdon Press, Nashville, TN, p. 23.

3 P. Enns, 2005, Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, Mich., p. 120 (emphasis in the original).

4 Wright, N T. Jesus and the Victory of God. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996, p. 243.

5 G.K. Beale, 2011, A New Testament Biblical Theology: The Unfolding of the Old Testament in the New, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 638.

6 P.W.L. Walker, 1996, Jesus and the Holy City: New Testament Perspectives on Jerusalem, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, p. 117.

7 The Kairos Palestine Document (2.2.1).

~

Recommended by: